I label some of my ideas as “moonshots”. In my mind, moonshots might be difficult but potentially enormously impactful ideas. Of course, there is a risk of being perceived as naive or ludicrously optimistic by the establishment. But I think it’s worth the reputational risk of sharing an ambitious idea which has at least a small chance of being extremely valuable.

Today: Market Problems

The fact that so many companies in the world are connected in some way to each other via a complex network of commercial relationships is tantalising to someone looking for high-scale solutions to tackle slavery and labour exploitation in supply chains. The intricate and ever-changing web of interactions and relationships is driven by incentive structures based upon product, cost, logistics and probably many others. Nobody designed this structure. It develops organically and it continues to change and adapt every second to meet consumer and business demands. As a system it’s very efficient. Capitalism means where there is a demand, markets drive companies to fill this gap with a relevant product or service.

This system results in behaviour that drives down cost to compete. In recent years, automation, improved management practices and supply chain solutions have continued to improve efficiency which has resulted in some commercial structures becoming extremely sensitive to cost. This has resulted in greater pressures on all companies to reduce their costs and has led to exploitation and poor working conditions in some countries. Exploitation of workers remains as stubborn as ever. (I’d recommend reading this article from HRW to get a sense of the challenge for suppliers)

Much of our collective response has been “top-down”. This means we have been applying pressure on big companies at the top of supply chains to be responsible for improving labour conditions of their suppliers further down the chain. Modern Slavery legislation and pressure from financial institutions are examples of this pressure. (The usefulness of pressure from consumers is questionable in my opinion. In fact ethical products may be a lucrative commercial opportunity for retailers, and sometimes there is little benefit to at-risk workers). Given this pressure, big companies are reacting to mitigate the legal and reputational risk.

Most of the attempts by big companies to tackle labour abuse in supply chains have been via a “brute force” approach involving painstaking work to develop “supply chain transparency” and attempting to tackle labour abuse, somehow, within each of those companies. This article isn’t intended to comment on the effectiveness of any particularly method that companies use to tackle labour abuse in a supplier company. Others have explored the issues and benefits of certifications, audits, unions, worker-voice solutions, etc. My interest is that this has demonstrated a market for services which try to tackle slavery in supply chains (albeit a largely immature market at the moment, in my opinion).

If you are a large company with, say, 5,000 first tier suppliers, it’s quite a job to check labour abuse of every factory of every supplier. It’s no wonder you might consider outsourcing the challenge of discovering abuse to audit companies. It’s even harder to check all of your tier two suppliers. (It’s hard to even find out who they are). In fact it quickly becomes prohibitively impractical for one company to do this (even if they outsource the problem) for their entire supply chain. Remember that much of the abuse happens in services separate to the core product supply chain. If a company claims profoundly to have supply chain transparency then ask about who their tier two suppliers pay to fix their waste pipe system. Or where they buy lubricant for their machinery. And who they pay to fix the factory roof. The supply chain focussed on a material product is a narrow part of a wider supply network. A supplier in financial distress may well contribute to labour abuse in ancillary services overlooked by buyers.

If a company claims profoundly to have supply chain transparency then ask about who their tier two suppliers pay to fix their waste pipe system. Or where they buy lubricant for their machinery. And who they pay to fix the factory roof.

Whilst companies’ CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) departments face the uphill battle of tackling labour abuse in thousands of companies across the world, there is another game afoot. Sourcing and procurement processes are about finding and selecting suppliers. These are usually different conversations with suppliers, this time based upon logistics, price and product. Suppliers remain under enormous pressure to meet the demands of buyers (or their agents) by meeting price and logistics expectations. This has led to a perverse dichotomy where buyers apply pressure on suppliers to increase their cost to improve labour standards at the same time as forcing price reductions to improve their commercial stance. As a supplier, responsible for hundreds of jobs, it’s inevitable the buyer’s deal is the priority. This is because there are plenty of other suppliers out there willing to take their place and their own employees jobs are at risk.

We are seeing behaviours resulting from fierce competition in a fluid market. When companies (or indeed governments) attempt to improve the ethical status of either their own organisation or their first line suppliers, they are actually increasing costs and therefore pushing against the market. This is why “brute force” approaches don’t easily scale. If a supplier improves labour conditions then the supplier’s costs go up. If that happens then finding customers is harder and the business shrinks, and already struggling workers end up jobless.

A scalable solution to tackling labour abuse across the world would cascade throughout supply chains and would be driven by market dynamics. A scalable solution would make it commercially attractive for a buyer to actively seek out the most ethical suppliers, therefore encouraging other suppliers to become more ethical to compete. A scalable solution would drive ethical behaviour from a fifth tier supplier without a first tier buyer knowing they even existed.

Future: Market Solution

So might a scalable solution look like?

When you look at enterprise commercial sourcing software, they will often use an index or score denoting the likely risks with a supplier. It does this because the sourcing software companies have talked to their customers (big companies) and found out that procurement professionals want concise quantifiable insights to help them make a judgement. An index is also interesting. It is naturally conducive to making comparisons between companies and potentially encouraging competition, (more on this later). What happens if the index was a measure of a supplier’s own effort and outcomes of tackling labour abuse, instead of just “risk”? Although I can understand that risk indices can be useful, an index that directly measures suppliers’ efforts to improve lives of workers will empower the supplier to make changes far more effectively than a generic risk index. Some more details on this later, but for now, let’s bank this as the first component of our new solution:

An index of a company measures the company’s own efforts and outcomes to tackle labour exploitation.

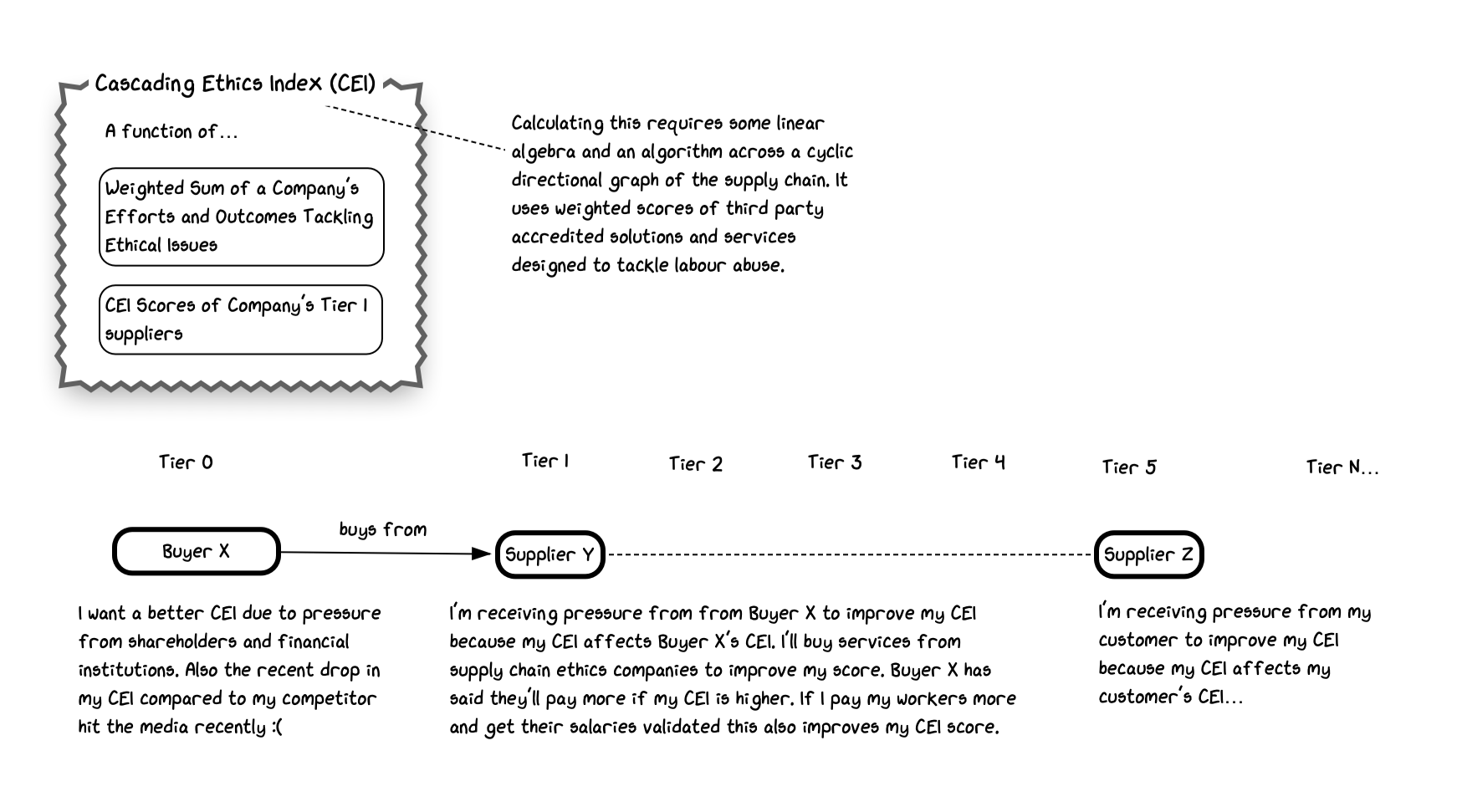

If it was possible to have such an index, then a supplier might be incentivised to tackle their own labour issues to please a buyer, but this would only work if the buyer was sufficiently interested in the value of the index. This is often where current solutions fall short. Right now, most index solutions are purely informational for buyers. The potential of today’s indices to affect real change is dwarfed by the stronger forces from procurement variables - price, logistics, etc. How could we tackle this? Well, let’s make our index not only a function of a company’s own efforts and outcomes to tackle labour abuse, let’s also make it a function of all of their first tier suppliers’ scores.

The index of a company is also a function of all of their first line suppliers’ indices.

This is where it gets interesting! Now, buyer X is interested in supplier Y’s score because it directly affects their own score. This is important for buyer X because they may have their own buyers who are also conscious of their scores, or indeed concerned financial companies who are investing in buyer X. Supplier Y is now interested in improving their score because it wants to avoid buyer X selecting a different supplier with a better score. Supplier Y might choose to improve their own efforts to tackle labour abuse within their workforce to improve their score. But they will also look at their own supply chain and put pressure on their first line suppliers to improve their scores. What’s happened is that the incentive to improve workforce conditions has cascaded through the supply chain. Buyer X, through its pressure on its first line suppliers has affected change much further down the supply chain. Importantly, buyer X has never needed to find out who its second tier suppliers are, let alone work out if they are abusing their workforce. The only thing Buyer X has needed to do is find out who its first tier suppliers are.

Now we need to cover some details here, but first, I think our index deserves a name: We’ll call it Cascading Ethics Index (CEI). You’ll note that the name doesn’t mention slavery, labour abuse, etc. This is because I believe this concept is equally applicable to encouraging businesses to tackle all manner of humanitarian and environmental issues! However, tackling modern slavery is my passion right now and I’ll continue to use this as the primary example of cascading ethical behaviour.

Our first challenge is that calculating the CEI of a company isn’t straightforward, (that would be too easy). One challenge is that buyer X / supplier Y relationships can also have the reverse relationship. For example, Apple might sell iPhones to Microsoft at the same time as Microsoft selling business software to Apple. So how do we calculate the CEI in this situation? Well, first it’s important to remember that a supply “chain” isn’t really a chain. It’s a complex web of relationships. Mathematically this is called a graph. Specifically, supplier relationships can be modelled as a directed cyclic graph. The calculation is a lot more complicated than simply adding up the average of all of the supplier’s indexes. The calculation becomes an algorithm and is beyond the scope of this article, but if linear algebra and Markov chains interest you then contact me and I’d be happy to discuss.

One of my frustrations has been that the other market in this story, the auditor/solution/certification market, isn’t performing particularly well today either (in my opinion!). There seems to be evidence (as well as anecdotal testimony from me talking with experts) that the impact of these products and services can sometimes be questionable. A solution to this will never be perfect - we can’t always audit the auditor. But, we can create an environment in which auditors and other solution providers compete to develop the most impactful solutions, instead of solutions that appeal most to their business customers. Firstly, remember that in this new solution, companies have an incentive to demonstrate efforts to tackle labour abuse in their own company. If a company purchases a worker-voice service from a service provider, then it might get a certain contribution towards their CEI score. If the outcome was verified independently then that contribution for that company would increase still further. The market for service providers offering products to tackle abuse would drive innovation because companies seeking to improve their own CEI score would seek the highest impact services from service providers - they would look for the lowest cost services that improve their score the most. Any rubbish audit solutions that had previously survived due to marketing more than substance would have low CEI weightings and would be driven out of the market. As long as the weighting was verified and the outcomes of company’s purchases folded into the CEI score, the market dynamic would improve the products and services proclaiming to tackle abuse.

To verify the weightings a network of non-profit organisations with specialisations in certain geographies and industries would be needed to assess the products and services from solution providers to determine their weighting. These non-profits would also be responsible for certifying product purchases and outcomes, that would contribute to companies’ scores. This is perhaps the most challenging aspect of this entire idea because it would require a step-change in the way products and certifications are evaluated and certified.

For the first time, procurement teams’ decisions would directly affect the external measure of their own company’s ethical status. Suppliers demonstrating efforts and impact to improve labour conditions would be rewarded with a higher CEI score. This would command a higher unit price for their products because their higher CEI score has commercial value to buying companies, whose own score would benefit. This adjustment to the balance of the market would draw in more money to organisations who today are beaten down by price. No longer would the procurement negotiations be based solely on commercial variables.

Hopefully you can see how this approach creates incentives that drive change. Indeed, because the CEI is a measure of effort and outcomes it creates a system of change. Because it is a market solution, it would be possible to codify new safeguards to verify necessary parameters such as first tier supplier lists and workers wages - verifications that would increase a company’s CEI. And so companies in developing counties would begin to pressure unofficial workforces to formalise their legal entities, pay tax and improve their own CEI scores. This is necessary for attestation by third parties authorised to verify contributions to the CEI.

The operation of a system like this has fascinating implications. Firstly, unlike risk indices today, it’s quite possible that the value of a company’s CEI could change every minute. This is because changes to scores near the bottom of the chain immediately affect companies further up the chain. Also, the algorithm means that changes to scores in companies who are direct competitors would also affect a score. The algorithm would automatically scale small differences between competing companies to maximise competition gradient, and therefore the speed of change. The algorithm could be surgically tuned for certain industries and geographies to maximise the competition so as to tackle the most pressing issues. And because trade crosses country borders, the effects would propagate to countries where driving improvements to labour conditions are most challenging. If a country banned CEI it would materially damage the competitive standing of all companies in that country. Conversely, there is an incentive for governments to encourage adoption of CEI to maximise their competitiveness.

Every score would be publicly available. A simple number that could be used for comparison by bankers and schoolchildren alike. The power of CEI is that it is a number that represents the ethical position of one company and its entire supply chain. Supply chain transparency shouldn’t be about identifying every company in your supply chain. It should be about the visibility of all of the combined efforts to tackle ethical issues in the supply chain.

The power of CEI is that it is a number that represents the ethical position of one company and its entire supply chain. Supply chain transparency shouldn’t be about identifying every company in your supply chain. It should be about the visibility of all of the combined efforts to tackle ethical issues in the supply chain.

The rapidly changing values of the CEI would help to make them interesting. For example, the declining CEI of a large company would not only indicate poor ethical standards, it could also indicate financial distress of an organisation unable to afford suppliers with a good CEI - something which investors would be very interested to know. As CEI tickers begin to appear on stock exchanges, it would unlock the strongest force available to tackle slavery and labour abuse in the markets - shareholders.

Hopefully this gives a sense of the potential power of cascading ethical behaviours using algorithmic incentives. As I mentioned earlier, I think this technique could be harnessed to encourage rapid change in companies’ ethics related to slavery, environmental issues and even corruption. But also note that there are a lot of operational and governance topics which go far beyond the scope of this article - please contact me if you’d like to know more or have any questions.